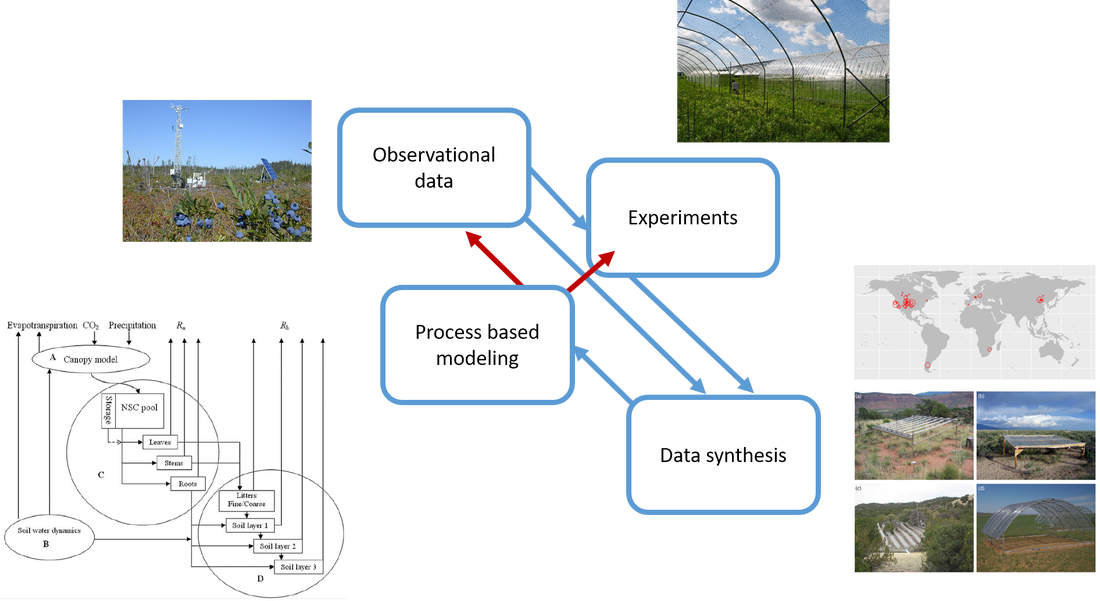

The lab's research focuses on responses of ecosystem processes, such as primary productivity and carbon sequestration, to environmental drivers, and how these responses are governed by plant community structure, population dynamics, and plant physiological and morphological characteristics. We primarily focus on grasslands around the world and how these vital ecosystems are changing under a changing climate, nutrient loads, and anthropogenic impacts like fire frequency and grazing intensity. To do this, the lab employs a wide range of empirical and quantitative methods, including making observations, conducting and synthesizing experiments, and running process-based ecosystem models. The latter allows me to identify knowledge gaps to inform future data collection efforts and experiments. By integrating across these different techniques, we are able to address pressing biological and ecological questions at scales relevant for land managers and policy makers.

Biodiversity as a driver of savanna recovery after compound extremes

in 2015 and 2016, an exceptional drought swept through southern Africa, causing massive plant mortality, widespread wildlife death, and other ecological damage. In a study our group conducted in Kruger National park, we found that this system had extraordinarily fast recovery rates due to the presence of a diverse plant community. Based on these observations, we are now conducting a five year experiment designed to (1) quantify the effects of co-occurring extreme events, namely extreme fire, herbivory, and drought, on ecosystem functioning; (2) identify the mechanisms behind biodiversity driven recovery after these extreme events; (3) incorporate these biodiversity mechanisms into mathematical models to make projections of savanna grasslands under future concurrent global changes and provide management tools for implementing strategies to maximize persistence of natural landscapes.

Scaling ecosystem stability from populations to meta-communities

Temporal stability of ecosystem functioning increases the predictability and reliability of ecosystem services, and understanding the drivers of stability across spatial scales is important for land management and policy decisions. We used species-level abundance data from 62 plant communities across five continents to assess mechanisms of temporal stability across spatial scales. We assessed how asynchrony (i.e. different units responding dissimilarly through time) of species and local communities stabilised metacommunity ecosystem function. Asynchrony of species increased stability of local communities, and asynchrony among local communities enhanced metacommunity stability by a wide range of magnitudes (1–315%); this range was positively correlated with the size of the metacommunity. Additionally, asynchronous responses among local communities were linked with species’ populations fluctuating asynchronously across space, perhaps stemming from physical and/or competitive differences among local communities. Accordingly, we suggest spatial heterogeneity should be a major focus for maintaining the stability of ecosystem services at larger spatial scales.

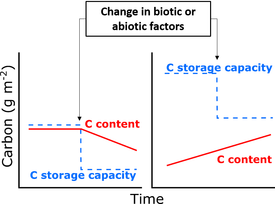

Identifying ecosystems vulnerable To future Carbon loss

The carbon capacity of an ecosystem is composed of how much carbon is entering the system (through plant growth), an how long that carbon stays in the system. Changes in climate, plant species composition, and land use are all likely to alter carbon capacity, and ecosystems that currently have carbon stocks close to their carbon capacity may be vulnerable to future C loss as their capacities change. By blending real-world data and mechanistic computer simulations, we are comparing the carbon capacity of multiple ecosystems with their current carbon stocks to identify ecosystems that may be particularly vulnerable to future carbon loss. We have identified hot and dry ecosystems as having high vulnerabilities due to low plant growth and high carbon turnover rates. This is especially true for monsoonal systems that have favorable soil conditions for carbon cycling for multi-week stretches during the growing season. These systems should be a high priority for management, policy and research focus.

Grassland sensitivity to precipitation

Above- and belowground plant responses to precipitation change across three grassland types. Climate models forecast alterations to both the amount of precipitation falling onto landscapes as well as shifts in the pattern in which this rain falls – coming in larger storms bounded by longer drought periods. Ecosystem sensitivity is the responsiveness of a system to alterations in the environment (i.e., how much biomass is lost due to a severe drought or grows during a wet year); patterns of sensitivity are important to understand if we are to predict responses to future climatic changes. We examined aboveground and belowground (roots) growth sensitivities to experimentally altered precipitation regimes in three different US grassland types. We found that more northern sites dominated by cool season grasses were insensitive to alterations in precipitation amount and pattern (many small vs. a few large events) in both years of the experiment, likely due to early growth patterns of the existing species when soil moisture is saturated from snow-melt. In both of our more southerly grasslands dominated by warm season grasses, we found different patterns of sensitivity depending on whether we looked at above- or belowground growth. This is important information as many past and current studies assume that above and belowground sensitivities are similar when this may not be the case. See Wilcox et al., 2015 for more information.

Plant community controls on ecosystem sensitivity: Central to understanding of earth’s C cycle is the functional relationship between precipitation and net primary production (NPP). Theory and empirical models predict that chronic changes in ecosystem water balance will alter aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) with the magnitude increasing over time as plant communities shift. However, ecosystem sensitivity (ANPP responses) to interannual precipitation variability is predicted to vary inversely with water availability. We increased water availability for two decades in native grassland and found that ANPP increased and ecosystem sensitivity decreased as predicted, but only initially. After 10-years, plant communities changed but ecosystem sensitivity unexpectedly returned to previous levels. In grassland sites with lower water availability and ANPP, ecosystem sensitivity never exceeded that in more mesic sites over 26-years, despite altered plant communities, showing that shifts in abundance of key plant species can stabilize precipitation-productivity relationships thus providing surprising functional resistance to climate change.

Photo credit: David Hoover

Photo credit: David Hoover

Interactions between fire and altered water availability on long term carbon and nitrogen pools: Chronic changes in climate and disturbance regimes may substantially impact ecosystem function and services worldwide with a forecast increase in periods of extremity pushing systems beyond critical thresholds. In productive grasslands, alterations in the water balance (wetter or drier soils) and more frequent fires are expected in the future. With more frequent fire, ecosystem models predict soil carbon (C) and nitrogen (N) to be reduced through the repeated combustion of aboveground biomass reducing C and N inputs. This loss may be exacerbated if increases in water availability lead to plants allocating more biomass aboveground. In a native mesic grassland, to quantify how extreme climatic and disturbance regimes will impact plant allocation patterns and soil biogeochemical properties in a native mesic grassland, we pushed this ecosystem well beyond past environmental conditions by increasing precipitation inputs (by 32%) for over two decades (1991-2013) while imposing the highest fire frequency possible (annual spring burning). We predicted (1) soil C and N would decline over this 23 year period with annual fire, and (2) this reduction would be much greater in sites with chronically wetter soils as shifts in biomass and production allocation patterns favored greater aboveground growth. Contrary to our prediction, annual fire led to no change in total soil N over time and a significant increase in soil C (52%). More surprisingly, annual fire combined with two decades of extreme growing season precipitation also resulted in a moderate increase in soil C (19%) although total soil N did decline by 14% under the combination of extreme climate and disturbance. The latter increase in soil C occurred despite greater annual losses of aboveground net primary productivity (ANPP) to fire in the extreme precipitation treatment (42%). No significant changes in tissue C:N were detected with precipitation additions and belowground net primary production (BNPP), root turnover rates and root:shoot ratios all were reduced, with each of these potentially reducing soil C. The results from this long-term imposition of extreme disturbance and climatic regimes suggest that soil C pools in this grassland are not likely to decrease as forecast from past modelling exercises but that N limitation may increase when such extremes are combined.

Nutrient controls on community dynamics and ecosystem functioning

Alterations of nutrient levels have the potential to drastically affect ecosystem functioning directly through changing of the availability of essential nutrients (e.g., nitrogen and phosphorus) as well as indirectly through restructuring of the plant community which can have its own effect on system productivity. I am involved in a number of collaborative projects examining the effects of nitrogen (N) and phosphorus (P) on various grassland ecosystems. In tallgrass prairie, we found that long-term chronic addition of N and P initially increased primary production on shorter time scales. However, over time these nutrient additions reduced the abundance of species that typically dominate natural prairie and increased abundance of more weedy species. After the community shift, primary productivity went back to normal levels but year-to-year variation increased. See our paper for more information.

Ecological stoichiometry as a predictor of species responses to global change drivers

In ecology, much research is dedicated to the search for general patterns applicable across broad categories (e.g., across space, species, individuals, etc.). Ecological Stoichiometry has been shown to be particularly useful in discovering some of these patterns. The stoichiometry of organisms (i.e., the amount of essential elements present in an organism) combined with information about how much of these elements the organism needs can tell us much about how it will respond in the future (here's a cartoony example: if I haven't eaten since breakfast and its 5pm, it is reasonable to predict that I will eat soon). One interesting characteristic which differs among plant species is stoichiometric homeostasis. This is more or less the "you are what you eat" principle. Species which have high homeostasis control the levels of their internal elements despite changes in the quantity of elements available in their environment; animals are highly homeostatic but plants vary widely in this ability. In a study done in 2011 at the Konza Prairie Biological Station, we found that more homeostatic plant species were more dominant in native tallgrass prairie under ambient nutrient conditions. However, we also found that under constant nutrient (nitrogen) enrichment, this relationship broke down and species which were less homeostatic began to dominate. This is likely due to high nutrient requirements of less homeostatic species but also higher growth rates when these requirements are met. Lastly, we found species more homeostatic for nitrogen were more resistant to long-term changes in precipitation regimes.